Si enim fallor, sum.

My previous post, Intersubjectivity is Key, made a few assumptions:

- Subjective viewpoints can contain truth.

- Subjective viewpoints can contain falsehood.

- The truthmaker is external to the subject.

I am fascinated by the idea of being wrong, especially given our culture’s current attitude toward it; Kathryn Schulz’s excellent TED talk is a fun but revealing treatment of one of the West’s foibles. The title of this post, “Si enim fallor, sum.“, is actually the earlier (and better) version of Descartes’ “Cogito, ergo sum.” Penned by Augustine, it means something like, “If truly I err, I am.” Lest the significance of this be lost, note that a computer cannot ‘know’ that it is wrong. It’s not even clear whether dogs can be truly sorry, or whether it is a conditioned response, kind of like p-zombies. (Admission: I have not extensively researched this.) What does it take in order to be able to know that you are wrong?

Let’s take an easy example: science. Wrongness means that my model of what would happen when I pull a lever predicts different results than what my senses tell me when I actually pull that lever. My subjective viewpoint is a model, the truthmaker is reality, and sometimes reality zaps me when I didn’t expect it. Intersubjectivity is helpful because sometimes I get locked into a world that seems to make sense and there aren’t enough zaps. Max Planck famously stated,

Let’s take an easy example: science. Wrongness means that my model of what would happen when I pull a lever predicts different results than what my senses tell me when I actually pull that lever. My subjective viewpoint is a model, the truthmaker is reality, and sometimes reality zaps me when I didn’t expect it. Intersubjectivity is helpful because sometimes I get locked into a world that seems to make sense and there aren’t enough zaps. Max Planck famously stated,

A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.

The shorter paraphrase is, “Science advances one funeral at a time.” According to St. Augustine, you might say that the old opponents have stopped being ‘I’s, or more briefly, they’ve stopped being. The philosophical/religious term being is a notoriously difficult one, but I just want to pick out the idea of living consciousness. Furthermore, let’s be precise with ‘living’: there needs to be some semblance of growth, whether that be in the realm of substance or in the realm of thought. A rock is not living (unless it’s a Horta); it does not adapt to better ‘match’ reality over time. Instead, it merely erodes and fractures, to perhaps play a part in life sometime in the future.

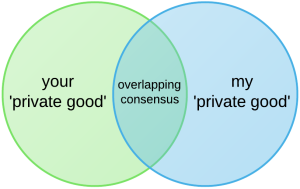

Now it’s time for the hard version: ‘the good’. In our age of moral relativism, you might say that there is no truthmaker for what constitutes ‘the good’ outside of each individual person. That is, there is no ‘common good’; there is only your ‘private good’, and mine. They might conflict, so we both sign a social contract which keeps us from bumping into each other too much. After all, we have some sort of overlapping consensus; the Venn diagram of our conceptions of ‘the good’ has a non-empty intersection. But maybe the overlapping section is 100% different for any given culture? C.S. Lewis, in The Abolition of Man, says no: the Tao is just another part of reality and one actually does find a lot of consensus among cultures on the basics, which in the appendix Lewis calls “general beneficence”, “the law of justice”, “the law of mercy”, “magnanimity”, etc. The Tao really doest exist outside of ourselves and is not merely defined by us, any more than a rainbow is defined by our perception of it.

Now it’s time for the hard version: ‘the good’. In our age of moral relativism, you might say that there is no truthmaker for what constitutes ‘the good’ outside of each individual person. That is, there is no ‘common good’; there is only your ‘private good’, and mine. They might conflict, so we both sign a social contract which keeps us from bumping into each other too much. After all, we have some sort of overlapping consensus; the Venn diagram of our conceptions of ‘the good’ has a non-empty intersection. But maybe the overlapping section is 100% different for any given culture? C.S. Lewis, in The Abolition of Man, says no: the Tao is just another part of reality and one actually does find a lot of consensus among cultures on the basics, which in the appendix Lewis calls “general beneficence”, “the law of justice”, “the law of mercy”, “magnanimity”, etc. The Tao really doest exist outside of ourselves and is not merely defined by us, any more than a rainbow is defined by our perception of it.

Can I be wrong when it comes to my conception of ‘the good’? Can I know that I am truly wrong? Do I have being in the moral domain? Wikipedia’s list of cognitive biases is a favorite of some on the internet, but do any of them have to do with ‘the good’? Let’s return to the issue of life. Life begets life after its own kind, while rocks just are (until they aren’t). I think it’s fair to say that scientific knowledge is alive. Newton’s three laws weren’t the be-all and end-all; we found ways that nature found to prove Newton wrong and we can do it, too. Thus we need better and better laws. The new is like the old; indeed, general relativity reduces to F = ma in low-mass, non-relativistic-speed scenarios. It’s like Newton’s creation had a kid and got out-performed. Good fathers are proud when their kids outdo them. So, I could ask whether a conception of ‘the good’, whether the Tao, can be alive.

Let’s see if we can find innovation in what Lewis called the Tao:

- Confucius: “Never impose on others what you would not choose for yourself.”

- Thales: “Avoid doing what you would blame others for doing.”

- Vidura: “… treat others as you treat yourself.”

- Jesus: “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.”

Is this the process of becoming “less wrong”, or is it merely a change in preference? Did the Silver Rule grow into/beget the Golden Rule? Is there a 5., like this guy thinks? In Abolition, C.S. Lewis gives guidance for how to tend the Tao:

Those who understand the spirit of the Tao and who have been led by that spirit can modify it in directions which that spirit itself demands. Only they can know what those directions are. (47)

Alasdair MacIntyre offers a more rigorous, although somewhat drier version in After Virtue:

By a ‘practice’ I am going to mean any coherent and complex form of socially established cooperative human captivity through which goods internal to that form of activity are realized in the course of trying to achieve those standards of excellence which are appropriate to, and partially definitive of, that form of activity, with the result that human powers to achieve excellence, and human conceptions of the ends and goods involved, are systematically extended. (187)

In other words: a practice produces real output that gives humans increased ability to pursue excellence, and can itself grow, so that future output continues to be better than past output. This concept of life is very present in science: if you want to see whether a given paper is likely to have a bead on the truth, see who cited it; see what ideas it begot. But perhaps some practices can cause one to start deviating from reality? This most definitely happens, but my suspicion is that investigation of such practices is that they start to die. It is as if detaching from reality detaches one from the source of life.

It is finally possible to describe how “Si enim fallor, sum.” can apply to morality. I can only err with respect to a practice, whether it is one of science, one of promoting excellence in all people, one of getting other people people to do what I want irrespective of their desires, or something else. This matches the intuition that breaking the rules isn’t always a bad thing: it’s only bad if you’ve thwarted something that matters. Or maybe: it’s bad if you’ve produced death in something alive, unless that ‘alive’ entity was death itself. I end with this wonderful poem by George Herbert:

| A DIALOGUE-ANTHEM. | ||||||||||

CHRISTIAN, DEATH.

|